The COVID-19 outbreak has had a detrimental impact to Pennsylvania’s economy. Governor Tom Wolf announced the state shutdown on Mar 19, 2020. In the week ending March 21, 2020, the weekly number of unemployment filings in Pennsylvania reached a record-high of 380,0001. After a 5-week stay at home order, the state’s total of jobless has surged to over 1.6 million or 24.7% of the workforce2. The halt of business likely has the biggest impact on less educated, lower-income, and minority workers. For example, pandemic related job loss is disproportionately higher among the low-income population3 due to low flexibility and the on-site nature of many low-income jobs.

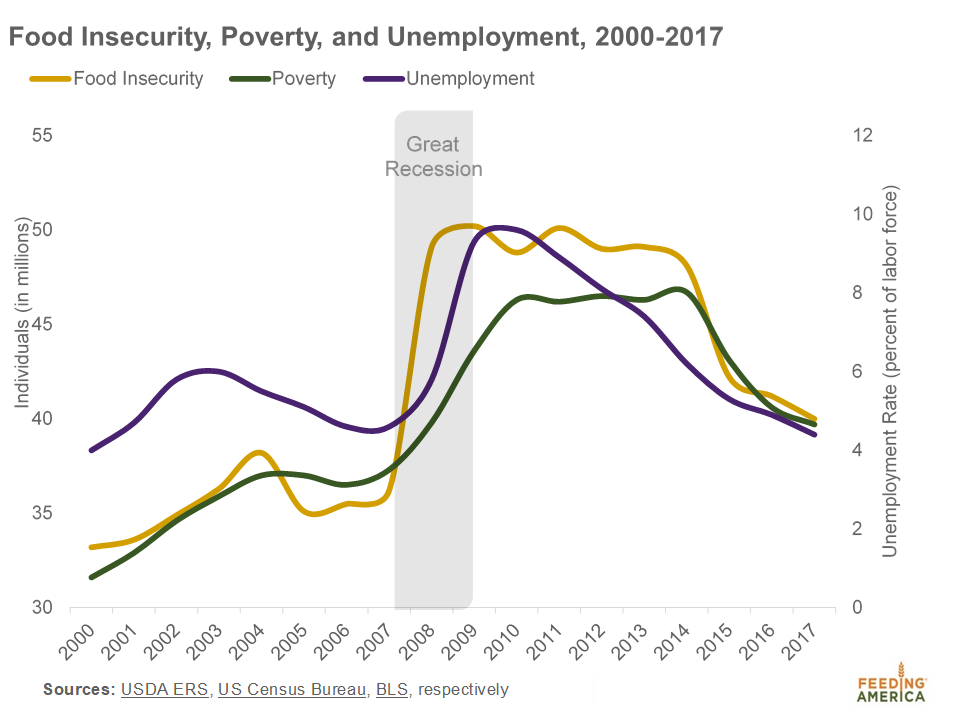

Unemployment and poverty go together. As a result of the rise of unemployment rate during COVID-19, in Pennsylvania food insecurity rates have increased from 11.1% in 2018 to over 33% in March 2020. Food insecurity is defined as a lack of consistent access to enough food for an active, healthy life. The increase in food insecurity due to COVID-19 is very similar to what happened during the 2007-2008 Great Recession (see Figure. The number of households being affected by food insecurity during the coronavirus pandemic will likely surpass the Great Recession high; and not surprisingly, the low-income will constitute the majority of those affected. As the figure illustrates, it took approximately a decade for the food insecurity rate to recover to its pre-recession level. COVID-19 has changed the way we live our lives, including how we grocery shop and what we eat. It is easy to imagine some substantial long-term impact on food access, hunger, and human health after the (hopefully) acute attack of COVID-19.

What has been done to tackle food insecurity in Pennsylvania? Many efforts have been made to monitor, evaluate, and address the food insecurity problem under COVID-19 from national4 and global perspectives5. We summarize these critical issues relevant to Pennsylvania, and discuss areas of concerns that remain unaddressed.

What has been done at policy and programmatic levels in Pennsylvania to tackle food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- Expand coverage of essential nutrition programs: On March 18, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) was signed into law by President Donald J. Trump6. FFCRA includes funding to support the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFEP), the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). Pennsylvania has issued, selected and received approval for a number of COVID-19 waivers for the SNAP, WIC, and Child Nutrition Programs for program flexibilities to ease program operations and to serve participants.

- Protect the children: Despite the nation-wide program flexibility waivers, Pennsylvania Department of Education has received the area eligibility waiver to maintain children’s access to the Summer Food Service Program and National School Lunch Program Seamless Summer Option7. Fresh fruits and vegetables will likely to be provided to children through the school food authorities operating the Fresh Fruits and Vegetable Program8.

- Maintain food supply: Beginning March 28, the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture (PDA) was approved to implement the Disaster Household Distribution that allows PDA to serve up to 772,500 individuals through the network of food banks using USDA Foods available on-hand9. The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) is implemented in Pennsylvania with the USDA’s approval giving food banks increased flexibility to serve those who are in need. The income eligibility paperwork will be temporarily waived under Pennsylvania’s Disaster Household Distribution program in order to receive USDA foods delivered to the state10.

- Increase income: On April 10, The US Treasury Department began to issue the first batch of direct deposits as part of the massive coronavirus relief bill. The exact amount that each individual receives will be based on several factors, like income, household composition, starting from $1200 for an individual. How many people will be eligible for the $1200+ check? According to USA Today’s estimation11, 92.7% of adults or about 7 million people in Pennsylvania. Unfortunately, $1200 may only cover a month’s rent and will likely not last for long.

What are the nutrition and health concerns related to food insecurity during COVID-19?

- Hidden hunger: “Hidden hunger” occurs when people able to consume enough calories, but lack essential micronutrients, such as vitamins and minerals which are required in small amounts but are important for health. In other words, hidden hunger is more of a diet quality problem than a quantity of food problem. Food insecure individuals and families need to cope with food hardship and sometimes have to sacrifice dietary quality (e.g. variety, nutrient-dense foods) over quantity (e.g. calories, energy-dense foods) to avoid hunger. But the risk of hidden hunger is increased when families must rely on unhealthy foods. Food insecure adults consume less vegetables, fruits, and dairy that are rich in micronutrients and promote good health12. Under the food crisis during COVID-19 and with the food substitution waivers in the WIC program13, prevalence of micronutrient deficiency will likely to be high; and consequences could be non-reversible if it occurs during critical life stages (pregnancy, infancy and young childhood).

- Physical health: It has been well-established that long-term food insecurity is related to the development of many adverse physical conditions14, 15, 16, 17, 18. Individuals who rely on SNAP, WIC, or other benefits often experience irregular eating patterns tied to the schedule of benefit distribution – as the month progresses and benefit money runs out, they may restrict their intake to try to make the food supply last until the next distribution. This type of irregular eating pattern can exacerbate chronic health conditions like diabetes.19 In addition, the constrained physical activities due to the stay-home order and poor medication compliance due to competing needs20 will further put the food insecure at higher risk of chronic conditions.

- Mental Health: COVID-19 is a big stressor, which causes a chain-reaction effect to increase stress in many different ways. Food insecurity is a stressor too. It increases mental distress21, 22, 23, 24 and decreases cognitive function25. For low-income people, chances are they have both stressors and their mental health may suffer.

Opportunities

Maintaining access to healthy, affordable food will be crucial to our recovery from the pandemic and its economic fallout. Essential workers in the food industry, from those working in food processing plants to grocery store clerks to fast food workers, have faced increased risk of exposure to COVID-19. Many of these essential businesses employ the lowest-paid workers in the country. Creative solutions will be needed to maintain the food supply chain while protecting workers from harm. With reduced demand from restaurants, programs that connect farmers directly to consumers may help ensure that food that has been produced gets to those who need it most. If schools remain closed, further infrastructure to distribute food to children who rely on the National School Lunch Program will be needed. Food assistance programs like SNAP and WIC will likely need to be further expanded with the unprecedented surge in unemployment. Digital technology such as videoconferencing could be used to deliver nutrition education. Building families’ skills around online grocery shopping, cooking, meal-planning, budgeting, and home gardening can help to make food budgets go further.

- 1Unemployment Insurance Weekly Claims Data. 2020. https://oui.doleta.gov/unemploy/claims.asp. Accessed April 28, 2020.

- 2Andrew Maykuth. The deluge of newly jobless workers is crashing the Pa. unemployment system as officials field 20,000 calls a week. https://www.inquirer.com/economy/unemployment-pennsylvania-coronavirus-…. Published 2020. Accessed.

- 3Mark A. Rothstein, & Meghan K. Talbott, Job Security and Income Replacement for Individuals in Quarantine: The Need for Legislation, 10 J. Health Care L. & Pol'y 239 (2007). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.umaryland.edu/jhclp/vol10/iss2/3

- 4Dunn CG, Kenney E, Fleischhacker SE, Bleich SN. Feeding low-income children during the Covid-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020.

- 5Van Lancker W, Parolin Z. COVID-19, school closures, and child poverty: a social crisis in the making. The Lancet Public Health. 2020.

- 6H.R.6201 - Families First Coronavirus Response Act. https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6201/text/eh. Published 2020. Accessed.

- 7Angela M. Kline. PA-CN-COV-AreaEligibility-Approval. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/PA-CN…. Published 2020. Accessed.

- 8Angela M. Kline. Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program during COVID19. https://schoolnutrition.org/uploadedFiles/5_News_and_Publications/1_New…. Published 2020. Accessed.

- 9Diane M. Kriviski. Approval of Disaster Household Distribution in Response to the National Emergency Declaration Due to COVID-19. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/PA-FD…. Published 2020. Accessed.

- 10Feeding Pennsylvania. Feeding Pennsylvania promotes and aids our member food banks in securing food and other resources to reduce hunger and food insecurity in their communities and across Pennsylvania. https://feedingpa.org/usda-approves-statewide-plan-for-disaster-food-di…. Published 2020. Accessed.

- 11Michael B. Sauter. Coronavirus stimulus checks: Here's how many people will get $1,200 in every state. USA Today Web site. https://www.usatoday.com/story/money/2020/04/28/how-many-people-will-ge…. Published 2020. Accessed.

- 12Hanson KL, Connor LM. Food insecurity and dietary quality in US adults and children: a systematic review–. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2014;100(2):684-692.

- 13Sarah Widor. Request for WIC Food Package Flexibilities In Response to COVID-19. https://fns-prod.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/resource-files/PA-CO…. Published 2020. Accessed

- 14Gucciardi E, Vogt JA, DeMelo M, Stewart DE. An exploration of the relationship between household food insecurity and diabetes mellitus in Canada. Diabetes care. 2009.

- 15Eisenmann JC, Gundersen C, Lohman BJ, Garasky S, Stewart SD. Is food insecurity related to overweight and obesity in children and adolescents? A summary of studies, 1995–2009. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(5).

- 16Larson NI, Story MT. Food insecurity and weight status among US children and families: a review of the literature. American journal of preventive medicine. 2011;40(2):166-173.

- 17Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Affairs. 2015;34(11):1830-1839.

- 18Laraia BA. Food Insecurity and Chronic Disease–. Advances in Nutrition. 2013;4(2):203-212.

- 19Seligman HK, Schillinger D. Hunger and socioeconomic disparities in chronic disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(1):6-9.

- 20Pooler JA, Srinivasan M. Association between Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participation and cost-related medication nonadherence among older adults with diabetes. JAMA internal medicine. 2019;179(1):63-70.

- 21Siefert K, Heflin CM, Corcoran ME, Williams DR. Food insufficiency and the physical and mental health of low-income women. Women & health. 2001;32(1-2):159-177.

- 22Liu Y, Njai RS, Greenlund KJ, Chapman DP, Croft JB. Relationships Between Housing and Food Insecurity, Frequent Mental Distress, and Insufficient Sleep Among Adults in 12 US States, 2009. Preventing chronic disease. 2014;11.

- 23Jones AD. Food insecurity and mental health status: a global analysis of 149 countries. American journal of preventive medicine. 2017;53(2):264-273.

- 24 Jessiman-Perreault G, McIntyre L. The household food insecurity gradient and potential reductions in adverse population mental health outcomes in Canadian adults. SSM-population health. 2017;3:464-472.

- 25Na M, Dou N, Ji N, et al. Food Insecurity and Cognitive Function in Middle to Older Adulthood: A Systematic Review. Advances in Nutrition. 2019.