The global Coronavirus pandemic of 2020 has had an unprecedented impact on the operations of national, state and local governments across all domains of public policy. In this post, we focus on the impacts to the criminal justice system (CJS) as of early April. Because this situation is evolving rapidly, the information presented here may change daily.

Although we focus on impacts within Pennsylvania, it is likely that at least some of the impacts discussed are generalizable to the CJS nationally, and perhaps even internationally. We examine system impacts resulting directly from efforts to contain the spread of the virus itself within the CJS, not from decisions made to shut down large sections of the economy and society in response. Decisions made to shut down large sections of the economy and society in response to the pandemic may have considerable downstream impacts on the finances of agencies within the CJS; future efforts could evaluate the longer term effects of the crisis on government revenues. We describe three core components of the CJS – Courts, Corrections and Policing – and present impacts to each as well as opportunities going forward.

Courts

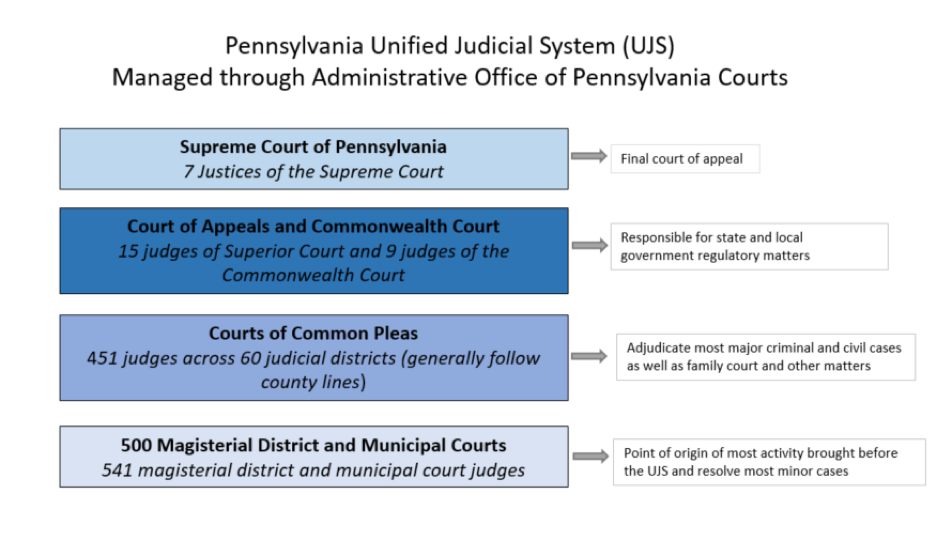

Courts operate on a variety of models across the country. States like Pennsylvania have unified court systems, where the courts are managed at the state level. Conversely, courts in states like Texas are largely devolved to the county level. In Pennsylvania, the Unified Judicial System (UJS) is managed through the Administrative Office of Pennsylvania Courts, under the ultimate authority of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. Figure 1 depicts the levels and responsibility within the PA UJS. The PA UJS system dockets approximately 2.5 million cases annually, or over 200,000 per month, 50,000 per week, or 10,000 for each day the court system operates. The UJS also generates approximately $460 million dollars in fines and other revenue per year, much of which is redistributed to state and local governments in PA.

The Supreme Court of Pennsylvania took several actions in response to the Coronavirus crisis.

March 16: The Court declared a statewide judicial emergency that closed the courts to the public through April 3 and suspended much court business to that date. This order also suspended most trials and pleadings until April 3. Essential court proceedings were permitted to continue, including (but not limited to) emergency habeas corpus hearings, juvenile delinquency detention, protection from abuse hearings, issuance of search warrants and other matters. This order appeared to grant the President Judge (PJ) of each court some degree of discretion in the application of this order. The Supreme Court’s April session was also postponed. Courts were urged to use “advanced communication technology” (e.g. videoconferencing) as far as legally and constitutionally permissible to expedite the conduct of some court business, such as filing of motions, while maintaining social distance between court actors.

April 1: The Court issued supplementary guidance on this closure order to clarify various questions that had been raised within the legal community and to extend the March 16th order through the end of April. Most notably, it appears that the order of April 1 grants additional discretion to the PJs to allow non-essential court business to the extent compatible with social distancing guidelines. It appears, however, that trials will not be held at least through the end of April. See these links for information related to the judicial order on the Coronavirus response:

http://www.pacourts.us/assets/files/page-1305/file-8846.pdf

http://www.pacourts.us/news-and-statistics/news?Article=1018

With respect to the impact of this order on the PA CJS, a suspension of many court activities for a period of six weeks will have a noticeable impact going forward, creating a considerable backlog.

Corrections

Corrections in Pennsylvania is made up of the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections (PADOC), which oversees state institutional corrections (e.g. “prisons”) and adult state parole, and local county jails and probation offices. Table 1 presents an overview of the PADOC.

Table 1: Overview of the PA DOC

| 25 State Correctional Institutions (SCIs) |

| 50 Community Correction Centers/Facilities (“halfway houses) |

| ~8,500 newly sentenced offenders annually |

| ~8,500 parole violators annually |

| ~47,000 inmates housed on a given day |

| ~20,0000 inmates released annually (~75% released on parole and remainder have served maximum sentence or are released by other mechanisms) |

County jails in Pennsylvania (as in most states) are entities of the county government and are not managed by state corrections. Of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties, 62 have their own jail; the remainder house their small inmate populations with neighboring counties. On a typical day, these county jails house approximately 31,000 inmates. The composition of the county jail population is different from that of the SCIs. While the vast majority of inmates in an SCI are sentenced offenders, at any given time half of the population of a county jail may consist of pre-trial or pre-sentenced detainees. These are people who have not yet been tried or bailed out, or who have been convicted but not yet sentenced. County jails will typically hold convicted inmates with sentences of two years or less; the others go to the PADOC.

Correctional facilities of any type can be particularly susceptible to the spread of disease, given the large numbers of people living in close quarters. Single cells are rare, with dining, exercise, dayrooms, education, work, religious services and other daily activities almost always in common areas. New inmates may arrive on a daily basis, correctional staff rotate in and out in shifts, and visitors are all potential sources of disease introduction.

At the time of this posting, the PADOC has reported seven cases of Coronavirus, at SCI Phoenix in Montgomery County. The response to the Coronavirus crisis within the PADOC to date has centered on several measures.

March 12: PADOC suspended all in-person visits to inmates for a two-week period.

March 25: March 12th order extended until April 10, and on April 9 extended indefinitely. To compensate for the loss of in-person visits, PADOC has increased the use of Virtual (Video) Visitation (VV) and free phone calls. While VV has been around for many years, never before has it been the only mode of visitation between inmates and their loved ones for an extended period of time. PADOC also enacted several other measures, such as enhanced screening of official visitors to the SCIs, a reduction on the number of official visitors, enhanced cleaning protocols, directing non-essential staff to work from home, issuance of Personal Protective Equipment (e.g. masks) to all staff and inmates, and other measures.

March 30: PADOC placed all SCIs into lockdown, giving inmates little opportunity to be out of their cells as compared to normal operations.

March 28: As a related quarantine effort, PADOC began using SCI Retreat, which had been in the process of closure, as a temporary quarantine facility, where all new male arrivals will be housed for 14 days before moving on to other SCIs as appropriate.

Other measures are being taken to expedite the release of inmates who are parole eligible and to limit returns to halfway houses and for parole violations, as well as limiting contact between parole agents and parolees. Most recently, talks are underway for legislation that would allow for the early release of as many as 3,000 lower level, lower risk inmates, especially those who are medically vulnerable. On April 10, the Governor signed an order establishing a Reprieve of Sentence of Incarceration Program to allow for the releases of selected inmates during the crisis. On April 15th, the first group of eight inmates were identified for release under this order. Other states have considered such measures, with New York announcing it would release 1,100 parole violators. Illinois will halt all new admissions. Similar measures are under consideration for the federal Bureau of Prisons.

More information on the PADOC’s efforts can be found here.

At the county level, the ACLU of Pennsylvania has filed an emergency petition to the PA Supreme Court to order the release of certain inmates from county jails, following the same parameters discussed above for the PADOC. Several county jails have already enacted such measures, including Dauphin, Erie, Lancaster, Northumberland, Montour and York. Allegheny County alone has released over 700 inmates, about one-third of its average daily population. Cumberland and Dauphin Counties are also using VV in place of in-person visits.

To further reduce risk of spread, the policy on cash bail within local jails and court systems for those who are awaiting trial is currently being reexamined. Individuals charged with crimes are remanded into custody until an arraignment hearing within the local court system, when cash bail can be set. However, there are large portions of current jail populations who are unable to meet these cash bail requirements (see this Prison Policy Brief for more information). The COVID-19 pandemic has renewed this call for reducing jail populations through bail reform, and Philadelphia for example has just revised current policies for cash bail systems due to this crisis.

As noted earlier, the operations of the courts have been greatly curtailed, with most trials and pleadings on hold for the time being. This has the effect of providing some relief for corrections, especially at the state level. PADOC receives on average 700 new court commitments per month. Thus, this pipeline of population growth is temporarily staunched.

Policing

At the state level, the Pennsylvania State Police (PSP) employs nearly 5,000 troopers and serves as the primary or secondary policing agency for two-thirds of Pennsylvania’s municipalities. In addition, there are over 1,000 local and other police departments in Pennsylvania, employing over 27,000 officers. Police, as front line first responders have few options to socially distance themselves from the public. Agencies are utilizing protective measures to ensure safety of their officers, including the use of masks, gloves, and person-to-person contact.

For the law enforcement response to the Coronavirus crisis, PSP has identified types of lower priority calls that could be resolved with limited or no in-person response. Presumably, other law enforcement agencies in Pennsylvania may follow suit with these measures, but little information is available yet. While these policy changes may have implications for public safety and criminal activity, behavioral experiences of officers with regards to their interaction with the public (whether perceived or actual) may have greater impacts on criminal activity within communities.

Indeed, new data from PSP indicate that crime in Pennsylvania is down 65% in the last half of March. This may be due to social distancing practices and the closure of businesses as well as changes in police enforcement. Still, this drop should provide at least some temporary relief to the courts and corrections, although the potential for a return to previous crime patterns after the lifting of the statewide lockdown is unclear

Opportunities

This is a rapidly evolving situation, with unintended and unpredictable consequences. Given the essential nature of law enforcement activities, police and corrections officers will continue to be at higher infection risk than average citizens. A shift to testing, infection containment, and treatment is inevitable for all CJS settings, particularly those where mitigation proves ineffective and outbreaks occur (e.g., jails and prisons). Within Pennsylvania, conversations on how to transition to new stages of the emergency are occurring both locally and statewide such that decisions will be made based on the rapidly developing situations on the ground. Finally, outcomes associated with these policy changes have the potential to inform future reform initiatives. These emerging situations and current contextual experiences provide a great need to continue to examine short and long term effects going forward.

Presumably, when the shutdown is lifted and the backlog in cases has been resolved, court operations can return to pre-crisis normality. Greater use of “advanced communication technology” can ameliorate some of the impact of the backlog. The traditional court culture, though, is strongly centered on in-person interaction between court officers (e.g. judges, District Attorneys, defense counsel, etc.) and the public in the courthouse setting. Thus, remote alternatives may at best provide partial relief for back-logged court systems. There remain unanswered questions regarding the effectiveness of this practice that evaluation researchers partners may be able to address in partnership with court systems.

In the current context, researchers who study policy also have new opportunities to partner with law enforcement entities including to identify effective police officer behaviors in critical situations and public perceptions of the effects of law enforcement activities on criminal activity and public safety.