This three-part post will describe my family’s experience as visiting scholars in Sweden during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this first part, to appropriately contextualize our experiences, I will describe the unique dynamics of Sweden including its health care system, its citizens’ trust in government, and population demographics. In the second post, I will provide a chronological description of Sweden’s response to COVID-19, including my husband’s personal experience with what was most likely COVID-19. In the final post, I will summarize where Sweden stands now and what can be learned from their experience. Through our personal experiences I hope to shed some light on what is happening in Sweden and to provide recommendations for the future.

Introduction

Our family of four, including my husband and two children, was in Sweden as visiting scholars from August 2019 to what was supposed to be summer 2020. We ultimately returned to the United States earlier than expected, in May 2020. Why? “Recovery’ for my husband from what was most likely COVID-19 has been challenging and scary, including his 40-hour stay in a Stockholm emergency room in late April.

Our story sounds like the butt of a bad joke. We went skiing in France in February 2020 for “sportlov”- Sweden’s sport week. My husband returned to Sweden, ill, with what turned out to be likely a case of COVID-19. While he sought testing, he was told that because he was in France, not Italy or China, they would not test him. We spent the next few months navigating the Swedish medical system and living through Sweden’s approach.

The Swedish health care system

In Sweden, access to healthcare is tied to one’s personnummer or personal identity number: the equivalent of a U.S. social security number but so much more. This number is used for everything from making a doctor’s appointment to registering a warranty on a product purchased at a store. After arriving in Sweden, it took us a few months to register and receive this number. Before we had it, it was difficult— if not impossible— to set up a bank account, establish reliable phone access, or even register for a discount card at the grocery store.

To access care normally, one calls a centralized telephone number. Dial “1177” and the triage nurse will listen to your concerns, identify where you live, and send you to the appropriate care. While the central government provides overall guidance, care itself is the responsibility of one of 21 regional councils across the countries, while elder care is the responsibility of one of the 290 cities. If someone needs to see a doctor in a non-emergency setting, they are sent to a vårdcentral- local “ward” to see a doctor. A visit often costs about $20 in a co-pay and health results tied to your personnummer.

Societal views on health and trust in government

We were struck by cultural norms around health in Sweden. Have the slightest sniffle? Stay home and certainly don’t work. Your child is ill? Keep them home from school.

This cultural focus is backed by official sick leave policies. Under normal circumstances, a person may take a sick day but is not paid for sick leave until the second day of leave (this changed post-COVID). They are then entitled to receive up to 14 days of sick leave pay from their employer; payments after this point are paid by the central government. Any payments beyond 7 days of leave require a doctor’s note.

Parental leave and allowance for caring for sick children is also generous. When a child is born or adopted, parents are entitled to a total of 480 days of paid parental leave (up to 240 days for each parent, with 90 days reserved exclusively for either parent). At age eighteen months, children are eligible for free pre-school; free schooling is provided for Swedish citizens through college.

For kids age 8 months to age 12 years , parents are entitled up to 120 days/year of a “temporary parental benefit” (paid leave) per child to provide care for a sick child.

In the workplace setting, this means who is working at any given time is fairly fluid. I had an interesting conversation one day with the person in charge of scheduling for Uppsala University’s Peace & Conflict Resolution Department. He described the intricacies of making sure classes were covered and student needs met despite the ever-shifting set of people on leave, both short and long term. Another colleague noted that people tended to “pitch in” to help cover for colleagues as they knew that a time would come when they needed help covering their commitments. This type of trust seemed to extend from the individual to the country level, at least pre-COVID.

Trust in authority

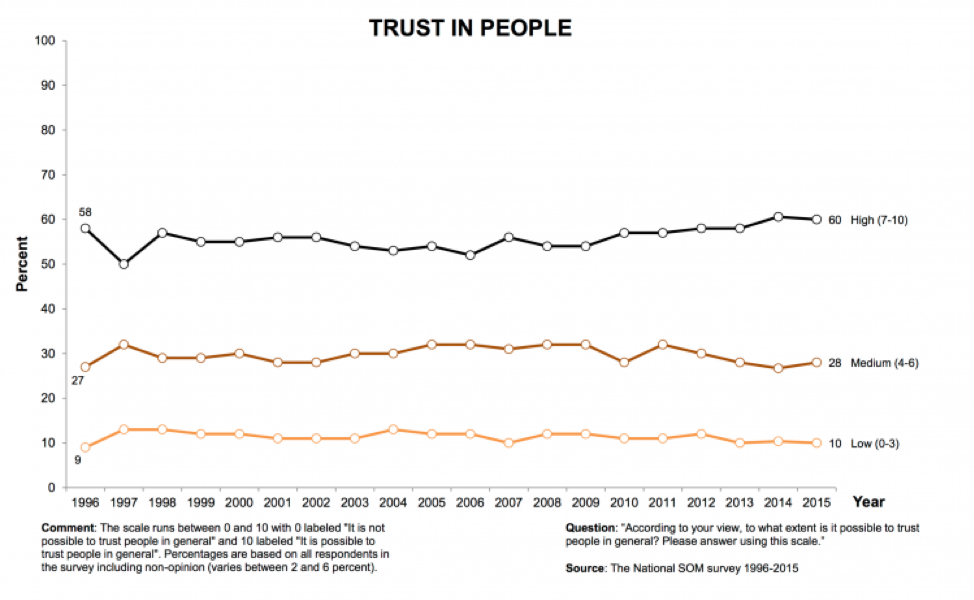

At least prior to the pandemic, Swedes have had some of the highest and most stable levels of “trust” in the world. According to “Our World in Data”, more than 60% of Swedes think that people can be trusted. This interpersonal trust has remained relatively stable over time as shown in one study from 1996 to 2015.

As the pandemic started to break and awareness moved from China to Italy to Europe writ large, there was a lot of discussion of how Swedish citizens “trusted” the government and that this would help in managing the COVID-19 response. In March 2020, the Local Sweden (an online newspaper written in English) published an article entitled "Sweden's coronavirus strategy is clearly different to other countries so who should people trust?" The article points out that there has long been a history of societal trust in government in what has been a relatively homogeneous country and where everyone received their news from the same sources. The article notes that today, however, there are far more people here from a variety of countries with different assumptions in government and different news sources.

Demographics

Sweden’s demographics have played an important role in pandemic management, both for the elderly and foreign background populations and for where people live.

As of 2017, 24.1% of Sweden’s population had a “foreign background”- either foreign born or with parents who were born abroad, with a big jump in the foreign population peaking in 2015 with migration and refugees, including from Syria. Today, of the ~10 million people living in Sweden, ~2.5 million are considered a "foreign population.” What is clear is that these population dynamics have been important to the management of COVID-19 in Sweden. In an article dated June 22, 2020, a recently released report found that people residing in Sweden, but born abroad, have been both at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 and for dying from it.

Like other countries, Sweden’s elderly population has also been hard hit. Approximately 20% of the Swedish population is age 65 or older, with 5.2% older than 80 and 1% older than 90 (as of 2019 ). Sweden municipalities provide elder care benefits to keep people in their homes as long as possible. Even so, approximately 87,600 people resided in “special housing in 2019.” As a note, as the pandemic broke, the definition of elder care facilities seemed to vary by country; this may be worthy of further research to determine the demographics of who resides in care facilities.

Of the total population of Sweden, 20% reside in the Stockholm region, the country’s capital. In Stockholm County, there are approximately 2.4 million people (as of 2019), again out of a total population of 10.3 million people. Early cases of the pandemic were identified in the Stockholm region, with overall case numbers the highest in this region (see blog post #3, coming soon).

Stay tuned for the second post in this series, where I will provide a chronological description of Sweden’s response to COVID-19, including my husband’s personal experience with what was most likely COVID-19.